|

the parish

of Whitechapel: prostitution and the victims of murder

|

Whitechapel

and prostitution

|

|

The

Whitechapel murders

|

|

The

victims of Jack the Ripper

|

|

Whitechapel murders home page

|

These

poor people had souls like anybody else

Comment

by the jury foreman at the inquest into the

death of Mary Nichols

As

reported in The Daily Telegraph; 18th September 1888

|

Whitechapel

and

prostitution

|

The Whitechapel

district of London at the end of the nineteenth century was generally regarded as being a ‘horrible black labyrinth, reeking from end to end and

swarming with human vermin, whose trade is robbery and whose recreation

is murder’. While such was apparently true for some areas, as a

generalisation it was inaccurate. The Poverty Map of 1889 certainly

showed many streets with inhabitants described as ‘lowest class -

vicious semi criminals’, or as ‘very poor – casual, chronic

want’, but these were often sharply juxtaposed with streets populated

by ‘middle class - well to do people’, and others by inhabitants

with ‘fairly comfortable - good ordinary earnings’, although the

majority of streets seemed to be a mix of types. The classification of

‘poor’ on this map corresponded to an income of 18s to 21s a week for a

moderate family but there were many who earned far less than that.

A survey of pauperism in London in 1869

revealed that within the Metropolis

(population 2,802,000 in 1861) there were no fewer than 34,609 paupers

indoors and 103,954 paupers outdoors making a total of 138,563. In

Whitechapel in that year there were 1192 adult and children paupers

indoors and 1234 adult and 1700 children under 16 paupers outdoors

making a total of 4126 for the parish.

The conditions undoubtedly provided

contemporaneous writers with an endless opportunity for florid prose. Whitechapel and thereabouts

was described as a maze of courts and narrow

streets of low houses, nearly all the doors of which are open. The image

is one of streets teeming with ragged individuals for whom alcohol

consumption was

preferable alternative to food and lodgings. People appeared to exist

rather than live within and among houses that were black and grim and

lodge within rooms that are described as being clean compared with the

guests.

One commentator observed areas to be;

‘Black and noisome, the road

sticky with slime, and palsied houses, rotten from chimney to cellar,

leaning together, apparently by the mere coherence of their ingrained

corruption. Dark, silent, uneasy shadows passing and crossing - human

vermin in this reeking sink, like goblin exhalations from all that is

noxious around. Women with sunken, black-rimmed eyes, whose pallid faces

appear and vanish by the light of an occasional gas-lamp, and look so

like ill-covered skulls that we start at their stare.’

Another

observer reported that;

‘Some

years ago, it was fashionable to "slum" - to walk gingerly

about in dirty streets, with great heroism, and go back West again, with

a firm conviction that "something must be done." And something

must. Children must not be left in these unscoured corners. Their

fathers and mothers are hopeless, and must not be allowed to rear a

numerous and equally hopeless race. Light the streets better, certainly;

but what use in building better houses for these poor creatures to

render as foul as those that stand? The inmates may ruin the character

of a house, but no house can alter the character of its inmates.’

An insight into the lives of

the poor comes from the very eloquent summaries of the coroner, Wynne E

Baxter who presided over the inquests of several of the Ripper victims. In

particular, he made some very evocative comments at the conclusion of

the inquest into the death of Annie Chapman. Of Chapman’s life he said:

‘She [Chapman] lived principally in the common lodging houses

in the neighbourhood of Spitalfields, where such as she herd like

cattle, and she showed signs of great deprivation, as if she had been

badly fed. The glimpse of life in these dens which the evidence in this

case discloses is sufficient to make us feel that there is much in the

nineteenth century civilisation of which we have small reason to be

proud; but you [the jury] who are constantly called together to

hear the sad tale of starvation or semi starvation, of misery,

immorality, and wickedness, which some of the occupants of the 5000 beds

in this district have every week to relate to coroner’s inquests, do not

require to be reminded of what life in a Spitalfields lodging house

means.’

And of the place where

Chapman was murdered he said:

‘This

place is a fair sample of a large number of houses in the neighbourhood.

It was built, like hundreds of others, for the Spitalfields weavers, and

when hand-looms were driven out by steam and power, these were converted

into dwellings for the poor. Its size is about such as a superior

artisan would occupy in the country, but its condition is such as would

to a certainty leave it without a tenant. In this place seventeen

persons were living, from a woman and her son sleeping in a cat’s-meat

shop on the ground floor to Davis and his wife and their three grown-up

sons all sleeping together in an attic. The street door and the yard

door were never locked, and the passage and yard appear to have been

used constantly by people who had no legitimate business there. There is

little doubt that the deceased knew the place, for it was only 300 or

400 yards from where she lodged. If so, it is quite unnecessary to

assume that her companion had any knowledge – in fact, it is easier to

believe that he was ignorant both of the nest of living beings by whom

he was surrounded, and of their occupations and habits. Some were on the

move late at night; some were up long before the sun.’

Shelter for those lucky enough to be able to afford a bed for the

night was provided by single rooms in lodging houses, many subdivided

for that purpose and offering little by way of facilities. Those

men and women who could not afford to sleep in a bed in a lodging house

would end up at the casual ward of the workhouse or on the street. The

casual ward provided temporary shelter in the form of ‘dormitories set

out like barracks’ in exchange for work such as picking

oakum – the loose fibre obtained by teasing out old ropes which was then sold to ship-builders for mixing

with tar and use as caulking.

Henry Mayhew wrote on the matter of labour and the poor around the

middle of the nineteenth century. He convened a meeting of needlewomen

and slop-workers in order that he could investigate their income. The

women revealed their lives of poverty and of prostitution as they spoke

at the meeting:

‘I am a slop-worker, and

sometimes make about 3s 6d a week, and sometimes less. I have been drove

to prostitution, sometimes, not always through the bad prices. For the

sake of my lodgings and a bit of bread I’ve been obligated to do what

I am very sorry to do, and look upon with disgust. I can’t live by

what I get by work. The woman who employs me and several more besides,

gets 11d and 1s a pair for the trousers we make, and we get only 4d or

5d. We can’t do more than a pair a day, and sometimes a pair and a

half. It’s starving. I can’t get a cup of tea and a bit of bread. I

was married, and am left a widow, and have been forced to live in this

distressed manner for the last four years. I’ve been to several

different people to get work but they are all alike in taking advantage

of our unfortunate situation.’

‘I am a shirt-maker and make about three shirts a day, at 2¼d apiece, every one of them having seven button holes. I

have to get up at six in the morning, and work till twelve at night, to

do that. I buy thread out of the price; and I cannot always get work. I

sometimes make trousers; but I have not constant work with both put

together. I sometimes make 2s 6d a week; 3s is the most I ever made, and

I have to buy thread out of that. I am now living with a young man. I am

compelled to do so, because I could not support myself. I know he would

marry me if he could. He is a looking-glass frame maker. He has earned

nothing for the past three weeks. If he had the money I know he would

marry me.’

‘My firm belief before God and

man, is that three out of every four young women of London who do slop

work are obliged to resort to either private or public prostitution to

enable them to live. But I hope better things are coming at last, and I

hope that, public attention now being called to these matters, the

oppressed will be oppressed no longer. But I am sorry to say the good

are not always the powerful, nor the powerful always the good.’

It was apparent that most women in similar straights had no

change of clothing; had pawned everything that they could possibly pawn,

including their beds, shoes, and underclothing; that none had meat as part of

a meal on any day of the week from their own endeavours; and that several had

not eaten at all for periods of up to two days. The conclusion was that

one quarter of women who worked in these trades as a whole, and one half

of those who did not have a husband resorted to prostitution. Figures

for 1857 indicated that across the seventeen Metropolitan Police

Districts there were a total of 8600 prostitutes, of which 5063 were

classified as ‘Low, infesting low neighbourhoods.’ In

1868 the figures were a little improved with a total of 6515 prostitutes

across 20 Metropolitan Police Districts of which 4349 were ‘In low

neighbourhoods.’ Of this latter figure, 623 were active in the

Whitechapel police division and there were 126 places where they lodged.

By the provision of such a service one can only imagine that there can

have been no shortage of clients.

There is a temptation to think that

because Mayhew's meeting was concerned with investigating the low wages

earned by these women, they would be inclined to overstate their case.

However, I doubt that such is true and given the many similar and

supporting observations from other independent sources, the

descriptions of the miserable existence of these women was probably

depressingly accurate. Almost without exception they engaged in

prostitution out of absolute necessity rather than from choice.

It is interesting to note the two distinct categories of prostitution;

private and public. Public prostitution is self-explanatory and private

prostitution one imagines is more ‘relationship’ based but still

reliant upon the man giving money to the woman even though her sexual

availability is more along the lines of those in a more conventional

relationship. The comment of one woman is informative; ‘I have not

resorted to prostitution any further than with my young man. I still

keep company with him, and we wish to get married.’ The partners in

this relationship seem to spend much time together but their

independence and distance is obvious. Frequent talk of marriage and

husbands underlines the perception of these women that they were outwith respectability and somehow marriage would change their

circumstances. Often women continued with street prostitution while

living with a man - Eddowes had been living with the same man for seven

years in common lodging houses - but the men either did not know or did

not admit to knowing that their women continued to work the streets.

John Kelly with whom Catharine Eddowes lived claimed that he ‘did not know of

her going out for immoral purposes at night. She never brought me money

in the morning after being out at night,’ was his response. It is also

interesting that the population, even in rough areas, was to some extent

in denial about the existence of prostitution and several witnesses at

the inquests were emphatic that they were not aware of lodgings or yards

being used for ‘immoral purposes’ even though many took money for

lodging from the women.

Payment for the beds in common lodging houses

was on a daily basis with cash up front. The price of a single bed was 4

pence, and 8 pence a night could secure a double bed. The price for sex

on the street was probably no more than a few pennies; an extremely

cheap way to catch venereal disease and a pathetic income for the risk

of losing one’s life! There was no post mortem

evidence to suggest that any of the victims had contracted a venereal

disease but there was an absolute epidemic among the prostitute

population during the late eighteen hundreds with syphilis and

gonorrhoea prevalent.

Women were allowed to take men back with them to

the common lodging house and there they could presumably spend the

night. But if a prostitute needed to earn more money then

she would need to work the streets and engage with as many clients as

she could find. Staying out late at night, even when a woman had secured

her lodgings, was not considered unusual and in the words of the coroner

at the Elizabeth Stride inquest prostitution was, ‘an offence very venial among

those who frequented the establishment [common lodging house].’

Those prostitutes not having a bed to use would have to have sex on the street. It is clear from

testimony during the inquests that many prostitutes knew of places they

could use that afforded relative seclusion. Quiet streets, yards,

passages, alleys and courts were all likely places to use if a room were

not available. Prices inevitably reflected this and the sex act on the

street was unlikely in most cases to involve any horizontal activity;

more likely, the act would take place against a wall giving rise to the

slang reference to a prostitute as a ‘twopenny upright’ which

reflects both the price and the attitude of the encounter.

Each of the supposed Ripper

victim’s was unmarried and lived on and off in common lodging houses

with the exception of Kelly who had the luxury of her own room.

Throughout the inquests there was constant reference to the victims’

unstable existence and there was much about their lives that was so

negative as to necessitate a measure of invention in order to bring a

little colour into an otherwise very grey world. For several of the

victims, stories that they told about their lives proved to be untrue.

The women were constantly on the move from one house to another at all

hours of the day and night. They were in and out; one minute supping

beer in the company of faces they recognised then consorting with

faceless paramours the next. They had no alternative but to flirt with

danger in the desperate pursuit of subsistence; for many women it ended

in premature and violent death.

|

Back

to top

The

Whitechapel murders

|

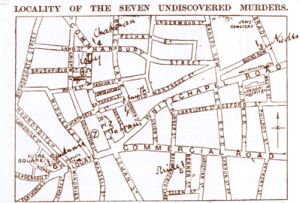

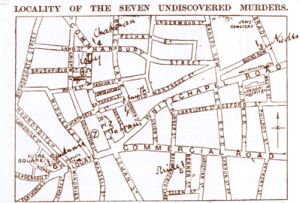

The Metropolitan

police defined eleven murders that at some stage looked as though they

may have been attributable to the serial killer known as Jack the

Ripper. To cite their information the full list of possible victims is

as follows:

|

DATE

|

VICTIM

|

CIRCUMSTANCES

|

|

03 April 1888

|

Emma

Elizabeth Smith

|

Assaulted and

robbed in Osborn Street, Whitechapel. Died the following

day

|

|

07 August

1888

|

Martha Tabram

|

Murdered

George Yard Buildings, George Yard, Whitechapel

|

|

31 August

1888

|

Mary Ann Nichols

|

Murdered

Buck’s Row, Whitechapel

|

|

08 September

1888

|

Annie Chapman

|

Murdered rear

yard 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields

|

|

30 September

1888

|

Elizabeth

Stride

|

Murdered yard

side of 40 Berner Street St Georges-in-the-East

|

|

30 September

1888

|

Catharine

Eddowes

|

Murdered

Mitre Square, Aldgate, City of London

|

|

09 November

1888

|

Mary Jane

Kelly

|

Murdered 13

Miller’s Court, 26 Dorset Street, Spitalfields

|

|

20 December

1888

|

Rose Mylett

|

Murdered

Clarke’s Yard, High Street, Poplar

|

|

17 July 1889

|

Alice

McKenzie

|

Murdered

Castle Alley, Whitechapel

|

|

10 September

1889

|

Female torso

|

Found under

railway arch Pinchin Street Whitechapel

|

|

13 February

1891

|

Frances Coles

|

Murdered

under railway arch Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel

|

All of the above murders remained unsolved but that alone is no reason

to assume that they were all conducted by the same person, for probably

they were not. Over the years and largely as a result of the Macnaghten

Memorandum of 1894 in which the Chief Constable Sir Melville Macnaghten

made known his beliefs, the list has been reduced to five likely Ripper

victims. Mary Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catharine

Eddowes, and Mary Kelly have become the generally accepted victims of Jack the

Ripper.

Because of the immediate similarities, these five cases were a good basis

upon which to make an analysis of crime scene and post mortem findings

and a comprehensive tabulation of this data has been undertaken and

reported elsewhere.

After considering the data in detail in the following pages I shall then

compare the killer’s signature components with what details are

available for the remaining Whitechapel murder victims. In addition, and

largely following attempts by others to identify The Camden Town Murder as a

Ripper victim I shall also consider in some detail at the murder of Emily

Dimmock:

|

DATE

|

VICTIM

|

CIRCUMSTANCES

|

|

12 September

1907

|

Emily Dimmock

|

Murdered 29

St Paul’s Road, Camden Town

|

|

Back

to top

|

The

victims of Jack the Ripper |

This

sections gives brief details about the five victims commonly attributed

to Jack the Ripper. These five murders shared several common features

and will be examined in greater detail later. Nichols, Chapman,

Stride, Eddowes, and Kelly are known as the canonical victims because

they supposedly form series that is generally accepted and authoritative.

However, this group was established largely on the basis of the

Macnaghten report of 1894, which listed these five women as victims of

the Ripper on somewhat arbitrary

grounds.

|

| |

Mary

Ann Nichols - aged 43

At the time of her death Nichols wore a black straw bonnet trimmed with black velvet, a reddish brown ulster with large brass buttons, a brown linsey frock, white flannel

chest cloth, black ribbed wool stockings, two petticoats (one grey wool,

one flannel and both stencilled on bands 'Lambeth Workhouse', brown

stays (short) flannel drawers, and men's elastic (spring) sided boots

with the uppers cut and steel tips on the heels.

Nichols' possessions when her body was

discovered were; a comb, a white pocket handkerchief, and a broken piece

of mirror.

|

|

| |

Annie

Chapman - aged 47

At the time of her death Chapman wore a long black figured coat that came down to her knees, a black

skirt, a brown bodice, another bodice, 2 petticoats, a large pocket worn

under the skirt and tied about the waist with strings (empty when found,

lace-up boots, red and white striped woollen stockings, neckerchief

(white with red border - folded tri-corner and knotted at the front of

her neck), three brass rings (missing after the murder)

Her possessions were; a scrap of

muslin, one small toothcomb, one comb in a paper case, a scrap of

envelope containing two pills |

|

|

|

Elizabeth

Stride - aged 44

Stride wore a long black

cloth jacket (fur-trimmed around the bottom with red rose and white

maiden hair fern pinned to it), black skirt, black crepe bonnet, checked

neck scarf knotted on the left side, dark brown velveteen bodice, 2

light serge petticoats, white chemise, white stockings, spring-sided

boots.

Her possessions were; 2 handkerchiefs,

a thimble, a piece of wool around a card. In the pocket of her

underskirt were the following; a key (as of a padlock), a small piece of

lead pencil, six large and one small button, a comb, a broken piece of

comb, a metal spoon, a hook (as from a dress), a piece of muslin, one or

two small pieces of paper. She was found clutching a packet of

cachous in her hand.

|

|

| |

Catharine

Eddowes - aged 46

When found, Eddowes was wearing a

black straw bonnet in green and black velvet with black beads and black

strings worn tied to the head, a black cloth jacket trimmed around the

collar and cuffs with imitation fur, a dark green chintz skirt with

three flounces, a man's white vest, a brown linsey bodice, a grey

stuffed petticoat, a very old alpaca skirt (worn as undergarment), very

old ragged blue skirt with red flounces (worn as undergarment), a white

calico chemise, no drawers or stays, a pair of men's lace-up boots

(right boot repaired with red thread), a piece of red gauze silk worn as

a neckerchief, a large white pocket handkerchief, a large white cotton

handkerchief, 2 unbleached calico pockets with tape strings, a blue

stripe bed ticking pocket, brown ribbed knee stockings (darned with

white cotton). He

possessions were; 2 small blue bags, 2 short clay pipes, a tin box

containing tea, a tin box containing sugar, an empty tin matchbox, 12

pieces of white rag, a piece of white coarse linen a piece of white

shirting, a piece of red flannel with pins and needles, 6 pieces of

soap, a small toothcomb, a white handled table knife, a metal spoon, a

red leather cigarette case, a ball of hemp, a piece of old white apron

with repair, several buttons and a thimble, two pawn tickets with false

addresses, a printed handbill, portion of a pair of spectacles and one

red mitten |

|

|

|

Mary Jane Kelly - aged 25

Mary Jane Kelly was murdered in her own

home - a rented single room. Her face was so badly mutilated by her

killer that an image of her features does not exist. The image shown is

from a drawing that appeared in the Illustrated Police News 17 November

1888 - there is, however, no reason to assume that it is a good, or even

approximate, likeness.

She wore only a chemise when she was

killed. Her clothes were folded neatly on a

chair and her boots were in front of the fireplace.

|

|

|

Post mortem images reproduced

by kind permission of the Metropolitan Police

|

|

Back

to top

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

home |

Whitechapel |

Whitechapel victims |

interpretation of findings |

how many victims? |

Mary Jane Kelly |

resources |

by ear and eyes |

© karyo magellan 2001-2006

|